The Mystery of the Fairy Circles of Western Australia

Exploring Nature’s Enigmatic Patterns

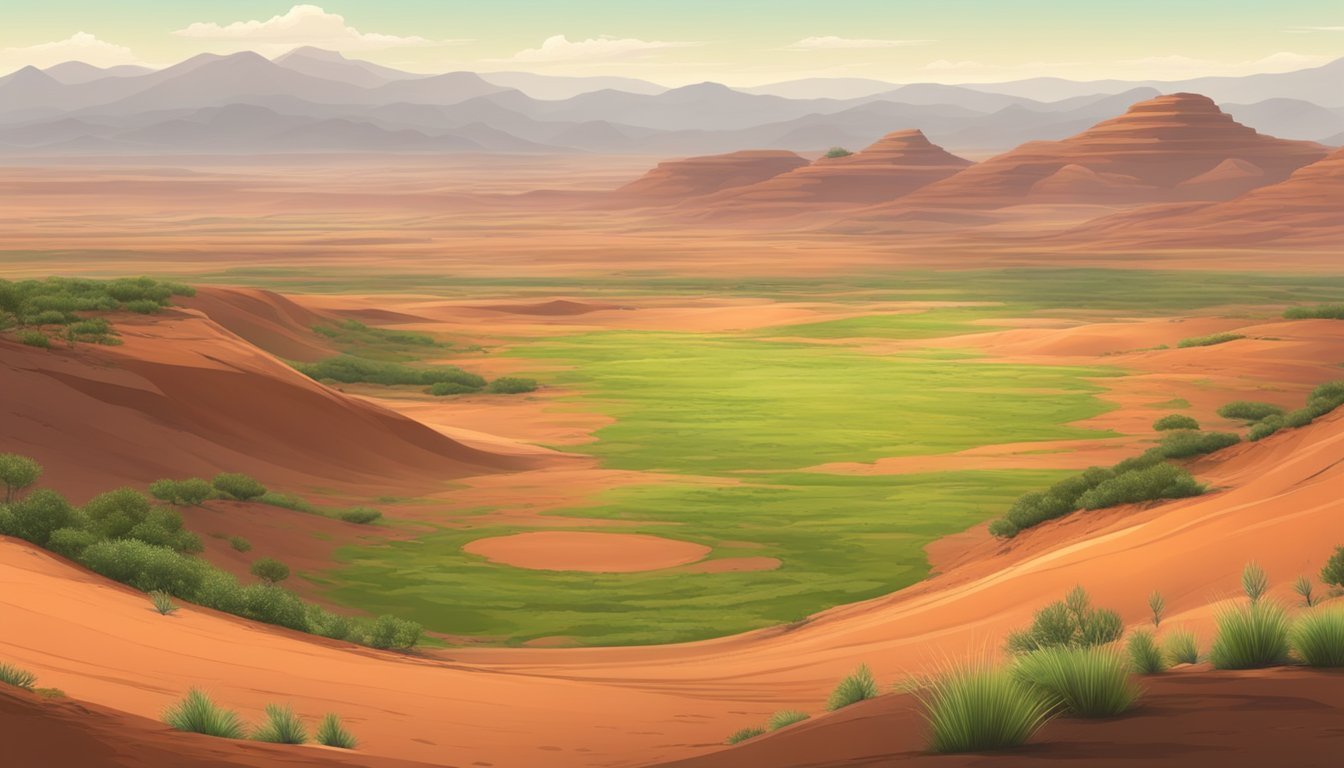

Across the vast deserts of Western Australia, perfectly round patches of bare soil known as fairy circles puzzle both scientists and locals. These mysterious formations, often surrounded by rings of grass, are thought to be the result of natural processes like plant competition for water and nutrients, with some insight drawn from Indigenous knowledge of the region.

Research suggests that Australia's fairy circles bear similarities to those in Namibia, yet their distinct geometric patterns and origins continue to spark debate. Anyone curious about Earth's unusual landscapes will find that the story of Western Australia's fairy circles reveals how much there still is to learn about the land's secrets.

What Are Fairy Circles?

Fairy circles are mysterious formations that stand out on Australia's arid landscapes. Scientists and local observers have documented their appearance, arrangement, and occurrence for decades, studying their physical traits and broader environmental context.

Visual Characteristics

Fairy circles appear as circular patches of bare soil, usually surrounded by a fringe of vegetation. Each circle is distinct, with sharply defined edges and a consistent diameter, often measuring several meters across.

The vegetation at the perimeter is typically taller and denser than elsewhere, forming a visually striking ring. These patterns often repeat with remarkable regularity, creating large fields of bare circles bordered by grasses.

Under certain conditions, these circles display a characteristic hexagonal arrangement, where each circle maintains roughly the same distance from its neighbors. This regular spacing can form large mosaic patterns visible from aerial views. The bare patches contrast sharply with the surrounding ground cover, making the circles easy to distinguish.

Distribution of Fairy Circles

In Australia, fairy circles are most commonly found in the desert regions, particularly across Western Australia and the Pilbara region. Extensive areas of arid or semi-arid land provide the conditions necessary for these formations to develop.

Maps and field surveys indicate that fairy circles are not random but tend to group in clusters or fields, sometimes extending for several kilometers. The phenomenon isn't limited to a single site; hundreds of sites have been recorded across Australian deserts, often in regions with similar soil and rainfall characteristics.

Australia is not the only place where fairy circles occur, but these formations are relatively rare outside the Namib Desert in Africa. The discovery of similar patterns in distant continents highlights the universal environmental factors that might drive the formation of these circles.

Historical Discovery

The presence of fairy circles in Australia was first noted by local Aboriginal peoples, who observed and integrated these features into their traditional ecological knowledge. Over time, Western scientists began to document the sites, comparing them to the better-known Namibian circles.

Early reports described the patches as unique landscape phenomena, sparking debates about their cause. Scientific interest increased as high-resolution satellite imagery revealed the widespread nature of the circles and their patterned distribution.

Recent research, supported by Aboriginal knowledge, has played a key role in uncovering the origins and persistence of these vegetation patterns. Collaboration between Indigenous experts and scientists continues to enhance understanding of these enigmatic circular formations.

Geographic Focus: Western Australia

Fairy circles in Western Australia are distributed across various arid and semi-arid landscapes. Seen in distinct regions, they highlight ecological differences and varying local influences such as soil, vegetation, and land use.

Pilbara Region

The Pilbara Region of Western Australia is characterized by rugged terrain, iron-rich soils, and sparsely distributed grasses. Fairy circles here generally appear as regularly spaced, bare patches within grassy plains.

These formations are most commonly found in Nyiyaparli country, where local Aboriginal people have long recognized and described their presence. Scientists have identified termite activity, especially from Drepanotermes harvester termites, as a major factor in the formation of these circles.

Climate patterns in the Pilbara, with infrequent but intense rainfall, influence both termite ecology and grass growth. The distinct vegetation patterns caused by the circles contribute to local biodiversity, creating microhabitats for various plant and animal species.

Western Desert Sites

In the Western Desert, fairy circles are abundant across vast arid landscapes. These sites are mainly within Warlpiri country and adjacent cultural lands. The circles often occur in large networks and can stretch over several kilometers.

Here, the bare rings are surrounded by bands of taller grass, which suggests competition for water and nutrients is a key part of their formation. The soils are typically sandy and nutrient-poor, which encourages the unique spatial patterns seen in the circles.

Local Indigenous groups have traditional knowledge relating to the circles. This knowledge is increasingly referenced by researchers to better understand the environmental history and ecology of the Western Desert sites.

Central Australia Context

Central Australia serves as a broader context for understanding why fairy circles are not limited to coastal or temperate areas. The region’s arid climate features extreme temperature swings, scarce rainfall, and sparse vegetation dominated by spinifex and other hardy grasses.

Studies in Central Australia compare the distribution of fairy circles in Western Australia to similar patterns found in Namibia, helping to clarify global drivers. The ecological similarities suggest that comparable processes, such as termite engineering and resource competition, may be at play.

These landscapes are mapped and monitored to track environmental change. This research gives insight into how arid ecosystems function and adapt, especially in relation to geomorphology and land management.

Ecological and Biological Factors

Fairy circles in Western Australia are shaped by a combination of environmental and biological forces. Patterns of vegetation loss, soil composition, and unique plant communities all play a part in how these circles form and persist within desert ecosystems.

Vegetation and Soil Changes

The circles appear as regularly spaced, barren patches with a bare pavement surface, sharply contrasting with the surrounding vegetation. Soil samples taken from within the circles frequently show altered texture and reduced organic matter compared to adjacent ground.

Several studies indicate that water infiltration rates can be higher inside the circles, which may limit plant establishment by creating drier conditions nearby. Loss of vegetation on these spots directly impacts how nutrients are cycled and distributed.

Scientists also propose that these zones result from a combination of plant competition and feedback between vegetation and hydrological processes. This regular spacing of bare soil patches is thought to reduce overlap in resource use among plants, leading to the ordered patterns seen across the landscape.

Spinifex Grasslands

Most fairy circles in Western Australia are found in spinifex grasslands. Spinifex grasses are well adapted to the arid conditions of the Australian desert and dominate much of the vegetation in these areas.

Patches devoid of spinifex are a defining feature of the circles. Around the edges, spinifex often grows in a dense ring, highlighting the sharp transition from bare soil to living grass. This boundary is usually well-defined and persists for many years.

The grasses respond to stress from competition for water and nutrients, which can drive the self-organization of circles over time. Their shallow, spreading root systems may contribute to maintaining open gaps by outcompeting seedlings that attempt to grow within the patches. This creates the striking, regular vegetation patterns that distinguish fairy circles from other desert features.

Termite Theory and Evidence

Research across Western Australia has linked the formation of fairy circles to termite activity, specifically focusing on how certain species engineer their environment. Multiple studies have moved beyond plant-based explanations, considering insect-driven processes as central to these striking patterns.

Spinifex Termites and Their Role

Spinifex termites are one of the dominant termite species in many Australian deserts. These insects actively clear vegetation in circular patches, creating bare, hard surfaces. This behavior is believed to help them manage resources and regulate their microenvironment.

Evidence for this role comes from observations of consistent, evenly spaced circles matching the distribution of spinifex termite colonies. Unlike plant competition theories, termite-driven models explain the persistence of the circles even in areas where rainfall is variable. Researchers have documented that these termites consume dead Spinifex grass and build nests beneath the surface, reinforcing the circle's structure over time.

Termite Pavements and Chambers

Beneath the surface of each fairy circle, “termite pavements” are a notable feature. These are layers of compacted soil created by termite activity as they clear and harden the ground for nesting. This action results in distinct, hardened circles clearly visible above ground.

Within and below these pavements are complex termite chambers. These chambers allow termites to store food and maintain a stable nest environment despite harsh external conditions. Some studies report that these nests can have several interconnected chambers, providing the colony with protection and access to resources. The hardened pavement also helps direct water toward the nest during rare rainfall events.

Termite Ancestors and Harvester Termites

Historical evidence and Aboriginal knowledge indicate that both harvester termites and the ancestors of modern termite species have shaped these formations for thousands of years. Harvester termites in particular are known for their ability to clear vegetation and build intricate underground networks.

Research led by biologists like Walter Tschinkel has highlighted the specialized adaptations of these termites. These include behaviors like dividing foraging duties and constructing large, cohesive colonies. Genetic and behavioral studies support a long lineage of environmental engineering by termite ancestors, influencing the persistence and regularity of fairy circles across Western Australia.

Key highlights:

Spinifex termites: vegetation removal and nest building

Termite pavements: hardened, compacted layers

Harvester termites: ancestral behaviors and long-term impact

Tschinkel: documented adaptations and influence on fairy circle formation

Research Insights and Scientific Debate

The study of fairy circles in Western Australia has drawn from scientific analysis, Indigenous perspectives, and modern technology. Research teams have integrated diverse data sources to better understand how these patterns form and persist in arid landscapes.

Recent Studies and Findings

Recent research has provided strong evidence that fairy circles in the Pilbara and other desert regions are not random. The patterns often appear as regularly spaced, bare, circular patches among vegetation. Studies have confirmed these are “pavement nests” created by Drepanotermes harvester termites.

Cross-cultural research has also been significant. Aboriginal knowledge contributed to identifying these sites and understanding their dynamics, upending earlier scientific assumptions. This collaboration has helped clarify that rather than resulting from plant competition alone, both biological and environmental factors are involved.

Scientists like Stephan Getzin have compared these Australian circles with those found in Namibia. Their work showed parallel processes, reinforcing the value of a global perspective. Researchers are now developing a global atlas of fairy circles to map and compare patterns worldwide.

Biologist Contributions

Biologists have played a key role in untangling the fairy circle mystery. They have analyzed the spatial distribution, soil properties, and insect activity at sites across Western Australia. The discovery that termite colonies create and maintain these circles was a turning point.

The work of Alan Turing is also relevant, as his mathematical models of pattern formation have informed analyses of circle arrangements. Biologists now use Turing’s principles to explain the self-organizing patterns seen in the desert.

The collaborative approach—combining biology, mathematics, and Indigenous knowledge—has moved the scientific debate beyond a single explanation. Detailed ecological surveys have also shown that these circles affect biodiversity, influencing the distribution of plants and animals in arid regions.

Use of Satellite Images

Satellite images have transformed how researchers approach the study of fairy circles. High-resolution imagery allows for large-scale mapping of patterns across remote desert areas. The identification and cataloging of thousands of circles would not be feasible through ground surveys alone.

Researchers use these images to analyze spatial arrangements, track changes over time, and validate site findings. Satellite data underpins efforts to build a global atlas of fairy circles, which supports cross-regional comparisons.

Image analysis has also made it easier to collaborate internationally and share findings. Scientists can now link patterns in Western Australia to those in Namibia and other regions, broadening understanding and sharpening debates within the scientific community.

Aboriginal Perspectives and Knowledge

Aboriginal people have observed and interpreted the fairy circles of Western Australia for generations, integrating them into cultural stories, language, and art. Their insights reveal ecological patterns often missed by scientific surveys, and provide context for features like Mulyamiji, Warturnuma, and Linyji.

Martu People and Traditional Understanding

The Martu people of Western Australia's Western Desert have lived near the regions where fairy circles are found. Their connection to the landscape includes a deep awareness of how these distinct vegetation gaps form and change. The Martu use their own terminology, such as warturnuma and linyji, to describe these features.

For the Martu, the circles are not just empty spaces; they are culturally meaningful locations embedded in local Dreaming stories. These stories often provide explanations not only for the existence of the circles, but also for the roles they play in the wider ecosystem. With generations of observation, the Martu have tracked how cycles of rainfall, plant growth, and animal activity influence the fairy circles.

Their traditional knowledge helps researchers understand how termite activity, particularly by spinifex termites (Drepanotermes species), and fire regimes contribute to the circles' formation. The knowledge passed down through oral traditions allows for detailed records of landscape change over long periods.

Warturnuma and Linyji

The terms warturnuma and linyji refer specifically to the fairy circles and similar vegetation gaps found in the arid lands. Warturnuma is commonly used by the Martu people to describe the hard, exposed patches often called “pavements,” while linyji is used for smaller or different types of gaps.

These features are not just physical phenomena but also carry significance in Martu land management and navigation. For example, warturnuma sites are regarded as landmarks and are often referenced in songlines and oral histories. Their consistent presence makes them reliable reference points.

Warturnuma and linyji also inform seasonal practices. The appearance of new gaps or changes in existing ones helps the Martu monitor the health of the land, track termite populations, and anticipate changes in local animal behavior, such as increased activity from grass-seed-eating marsupials like pamapardu.

Aboriginal Art Representations

Aboriginal art from the Western Desert often depicts fairy circles as concentric rings or dotted patterns across flat ochre or canvas backgrounds. These visual motifs represent not only the physical layout of the land but also layered meanings connected to ancestry, water sources, and Dreaming tracks.

In Martu paintings, features like warturnuma and mulyamiji (spinifex termite pavements) are included in complex map-like images that detail both topography and ecological knowledge. Artists may use color, repetition, and geometric shapes to illustrate the unique arrangement of the fairy circles.

This artistic representation is not only a form of cultural expression but also a method of documenting land features and passing on environmental knowledge. Community painting projects have helped bridge communication with scientists, supporting ethnoecological studies and increasing recognition of Aboriginal knowledge in contemporary research.

Ethnoecological Contributions

Aboriginal ethnoecologists, often working alongside non-Indigenous researchers, have played an essential role in identifying the causes and ecological significance of fairy circles. Their observational knowledge complements scientific methods, revealing how factors like termite activity, fire, and rainfall interact to create and maintain these unique landforms.

Ethnoecological studies, informed by terms such as warturnuma and linyji, help build more accurate ecological models. Aboriginal guides can point out subtle differences between surface types, document animal traces, and recall historical changes in land patterns.

Collaboration between Aboriginal experts and scientists has led to more thorough survey techniques and broader ecological insights. These partnerships demonstrate that Aboriginal knowledge is both scientifically valuable and vital for understanding the long-term stability and resilience of arid environments.

Comparisons with Fairy Circles in Namibia

Fairy circles in Western Australia have long invited comparisons to the well-known circles found in Namibia’s arid landscapes. Although these formations share some striking surface-level features, their contexts and underlying conditions reveal significant distinctions.

Similarities and Differences

Both Australian and Namibian fairy circles are marked by circular, barren patches devoid of vegetation, surrounded by a fringe of grasses. Satellite images and field surveys identify these features as prevalent in arid and semi-arid environments.

A key similarity is the regular spacing—circles are distributed in patterns that suggest ecological processes at work. In both regions, the circles appear over vast areas and differ in size, usually from a few to several meters in diameter. Studies using remote sensing found hundreds of sites in both Western Australia and Namibia with these characteristic patterns.

However, differences emerge in the composition of surrounding plant life and soil. Namibia’s circles occur mostly within grassy steppes dominated by Stipagrostis species, while Western Australia often features different grass species and soils. The development processes, though not fully understood, may be influenced by distinct local fauna, flora, and climatic conditions.

Environmental Factors in Namibia

Environmental factors shaping fairy circles in Namibia include low and variable rainfall, high evaporation rates, and sandy soils that drain rapidly. These conditions lead to intense competition for water among grasses, which may result in the observed vegetative gaps.

Research also points to the role of termites, particularly the sand termite Psammotermes allocerus, in altering soil properties and influencing water infiltration. This contributes to the persistence of bare patches within otherwise grassy areas.

Other environmental stressors—such as temperature extremes and nutrient-poor soils—add further complexity to the formation and maintenance of fairy circles in Namibia. These factors create a challenging setting where only certain plants can survive at the edges, reinforcing the bare centers and vegetated rims seen in the landscape.

Role of Australian Wildlife

Australian wildlife shape the unique environment of the desert, directly affecting and being affected by fairy circles. Interactions between species and conservation efforts play a critical role in maintaining this delicate ecological balance.

Desert Skink Interactions

The desert skink (Liopholis inornata) is a burrowing reptile native to the arid regions of Western Australia. This species often uses modified or sparse ground, such as those found around fairy circles, as suitable habitat for basking and constructing burrows.

Desert skinks rely on bare, compacted soils for quick access to prey and easier movement. Areas with fairy circles provide less dense vegetation, which allows these reptiles to detect predators more effectively and move without obstruction. The distinct layout of vegetation and open patches may influence where desert skinks are most commonly found.

Termite activity is also connected to both fairy circles and the skinks' habitats. Drepanotermes harvester termites often create “pavement nests” in these bare circles, shaping the microhabitat. The altered soil structure can indirectly benefit the skinks by fostering a consistent prey source and a favorable landscape for burrowing.

Australian Wildlife Conservancy

The Australian Wildlife Conservancy (AWC) actively manages many desert ecosystems where fairy circles are observed. Their conservation work includes monitoring populations of desert skinks and other reptiles, as well as maintaining habitats that support native flora and fauna.

AWC employs land management practices such as controlled burns, invasive species control, and scientific surveys. These methods help preserve ecological processes influencing the formation and persistence of fairy circles. By protecting native termite populations and vegetation, the AWC supports the unique interactions among species in these regions.

Table: AWC Key Activities Related to Fairy Circles

Activity Purpose Monitoring skink populations Tracks health of reptile communities Vegetation management Maintains open patches/grass balance Termite research Studies insect influence on soil

The role of organizations like AWC is essential for understanding and sustaining the intersection of wildlife and landscape patterns within the Australian desert.

Artificial Intelligence and Future Directions

Recent research into the fairy circles of Western Australia has used artificial intelligence to uncover patterns and possibilities that were not previously recognized. These advancements are reshaping how scientists identify and analyze these unique desert features, offering more accurate and efficient methods for large-scale ecological study.

AI in Pattern Analysis

Artificial intelligence has played a key role in identifying and mapping fairy circles. By processing satellite imagery and environmental data, AI algorithms can spot repeating patterns in vegetation that suggest the presence of fairy circles, even in remote or previously overlooked areas.

A 2024 study used machine learning to find 263 additional locations with fairy circle-like patterns across 15 countries. This approach reduces human error, speeds up analysis, and allows for more thorough coverage of vast landscapes.

Researchers now compare data across continents, thanks to AI-driven pattern recognition. This has revealed striking similarities between the circles in Western Australia and those in Namibia, supporting theories that self-organizing natural processes may be at work.

Advancements in Digital Research

Advances in digital tools have made it easier for scientists to collaborate and analyze ecological phenomena at a global scale. AI-driven platforms can handle large data sets from satellites, drones, and field surveys, making detailed comparisons practical.

Key benefits include:

Automated mapping of identified sites

Integration of climatic and soil data

Cross-referencing botanical information

These developments let researchers test new hypotheses quickly and share findings with the international scientific community. Digital research tools help spot environmental trends and predict where new fairy circles might emerge, increasing understanding of their formation and ecological impact.